Feeding the Algorithm: Nikocado Avocado and the Consumption of Self

“The world will ask you who you are, and if you do not know, the world will tell you.”

Imagine your middle school cafeteria. Think, specifically, of a day when something you said made the whole table laugh. Perhaps it was a moment of pride, or perhaps you said the wrong thing to the wrong table.

These moments, though fleeting, were formative. They nudged you toward an identity, sculpted through trial and error. Yet, today, this process has been radically altered. The whispers behind your back are now comment sections; approving nods, “likes”; and the cafeteria where we were fed is now a digital feed. In this algorithmic ecosystem, the stakes are higher, the cues more potent, and the feedback far less forgiving.

For a cautionary tale of this dynamic taken to its grotesque extreme, look no further than Nikocado Avocado, a YouTuber who turned food into spectacle and himself into an engorged embodiment of the digital age.

Nicholas Becomes Nikocado

Nicholas Perry was born in Ukraine, adopted, and raised in the United States. Like many young gay men, he yearned, deeply, for a sense of belonging. Early on, he gravitated toward music, dreaming of Broadway and mastering the violin. By his early 20s, disillusionment had set in. He abandoned his musical aspirations and moved to Bogotá, Colombia in 2014 to build a new life with Orlin Home, a man he met in a vegan Facebook group. Veganism became central to his identity and his fledgling YouTube channel, where he shared recipes and played violin.

But the soil of this new chapter was shallow. His health faltered on the vegan diet, and his enthusiasm for the subculture soured. By 2016, Nicholas felt unmoored, his dreams malnourished. Then, he stumbled across mukbang—a South Korean internet trend where creators film themselves eating enormous amounts of food while vocalizing the experience to their audience. Mukbang promised connection, creativity, and community. For Nicholas, it was the perfect excuse to change his diet.

Mukbang: Spectacle and Reflection

Mukbang, which translates loosely to “eating show,” began in South Korea as a way to simulate the communal joy of eating with others. As it grew, its appeal evolved. It became a spectacle of overindulgence, offering voyeuristic pleasure by amplifying food consumption to absurd extremes. Performers gorge themselves while narrating the experience, creating an intimacy that is paradoxically hollow.

For Nicholas, this hollow connection was intoxicating. His earliest videos reflected an earnest exploration of food and identity. But mukbang rewards excess, and the algorithm amplifies what draws clicks. Larger portions, messier meals, and more outrageous antics drew more views. Slowly, Nicholas disappeared beneath the folds of Nikocado Avocado, a persona crafted to feed an audience hungry for drama and indulgence.

Denial and Descent

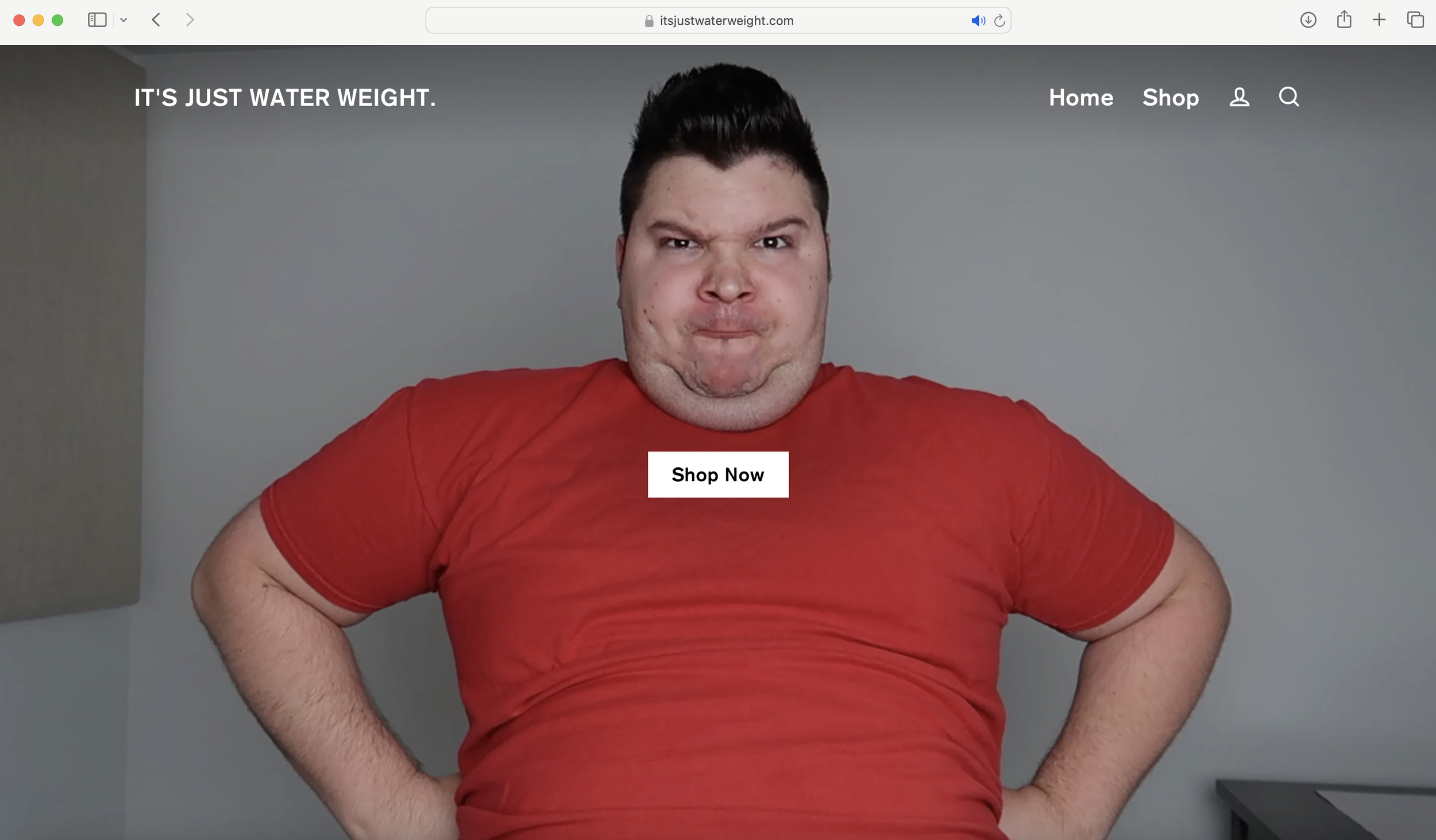

By 2017, Nikocado was already grappling with the consequences of his new identity. During a mukbang at Las Vegas’s Heart Attack Grill, he weighed himself on a public scale, laughing off its reading of 200 pounds as “water weight” and “stress.” The denial delivered more attention, so he leaned into it, titling videos “I’m Getting Fat and I Don’t Know Why” and “Say Hello to My Double Chin.”

Once Nikocado understood how the game worked, he worked it. As Nikocado, Nicholas began to gamify his own decline, turning his expanding body into clickbait. At first, he drew boundaries, claiming, “If I ever reach 300 pounds, I’m shutting down this channel.” But soon, his videos became countdowns to crossing each milestone: 300, then 400 pounds. Each thumbnail grew more grotesque, each title more tragic. “It’s just water weight” became his rallying cry and the slogan of his merchandise, encapsulating the mix of denial and performance that defined him.

The spiral deepened. Nikocado bought a chair rated for 400 pounds, turned marital disputes into content, and fed his (audience’s) appetite for destruction. His health deteriorated—sleep apnea, broken ribs, immobility—but the algorithm demanded more. Every tearful breakdown and grotesque meal tipped the scales further towards virality. Nikocado Avocado was no longer a character; at more than double his starting weight, Nicholas was outsized.

The Algorithm’s Appetite

Algorithms both fill our feeds and feed on us. They optimize for engagement, not well-being. Nikocado’s explosion serves as an exemplar — a self-reinforcing loop where his chaos fed the algorithm, and the algorithm fed his chaos. His audience was complicit, consuming his content as voraciously as he consumed his meals. They were rubberneckers in a digital pileup, shocked by his suffering but unwilling to look away.

Before you judge, you should know the same ropes are looping around you, too. Like Nicholas, we are shaped by the algorithms that govern our feeds. In fact, a survey conducted by Squarespace found that 60% of Gen Z believe their online self-presentation is more important than their in-person presentation.

The more we morph to match what’s on our screen, the more our screen matches, to morph us. We trim, twist and tailor ourselves, becoming caricatures designed to accumulate attention. The result is a collective erosion of the individual self, as we sacrifice authenticity for the fleeting rewards of digital validation.

Not convinced? Why is the fastest growing political party “unaffiliated”, the fastest growing religion “unaffiliated and why does the BBC now insist there are 100 genders more than they recognized several years ago? We are all fleshy hermit crabs in search of a new shell.

Epilogue: The Excavation

In 2024, a toned arm broke through the fourth wall. Nicholas? In a video titled “Two Steps Ahead,” he spoke to his audience through a panda mask and slowly revealed the 160-pound man underneath. He explained that he had been posting pre-recorded videos for years to maintain the fat fiction, describing the entire ruse as a “social experiment.” His words were laced with bitterness: “You are the ants.”

This dramatic unveiling was not merely a reclamation of his narrative but a vitriolic assault to seize back its authorship. Nikocado had consumed Nicholas. The audience had consumed Nikocado. But, in the end, Nicholas consumed the audience in a dazzling internet inversion. Where once he spiraled downward to please his audience, now he ascended, only the strings now in his slender fingers.

His narrative, one of victimhood turned “villainy” (his words), echoes a question society is starting to chant: Are we in control of our (digital) selves, or are we being controlled?

A Harrowing Harbinger

Nikocado Avocado’s story is grotesque but not exceptional. Our gluttony begot his, after all. He is, therefore, merely a reflection of our collective struggle to relocate our individual selves. His journey—from Nicholas to Nikocado to whatever lies ahead—is a larger-than-life version of the very dynamics responsible for transmuting people to products and then back again.

Mukbang, too, more than a meme; is a metaphor. It offers a microcosm of the perils of overconsumption—not just of food but of attention, validation, and identity. As we gawk at the spectacle, it’s less and less clear who is content and who is creator.

The lesson is simple but profound: To avoid being consumed we must reclaim the authorship of our stories. We must, as Carl Jung warned, “know who we are before the world tells us”. Otherwise, we may find ourselves, like Nikocado, encased in layers of a crowd-sourced identity, struggling to excavate who we were meant to be—if we ever knew at all.